Two Chapel Pond Slab climbs are missing historical markers, left behind by rock climbing legends

By Phil Brown

This summer I traveled west in part to seek out historical rock-climbing routes pioneered by the great Fritz Wiessner in the 1930s and 1940s. After returning home in mid-September, I climbed Wiessner’s route on Chapel Pond Slab–the Empress, first ascended in 1933–and made a disconcerting discovery.

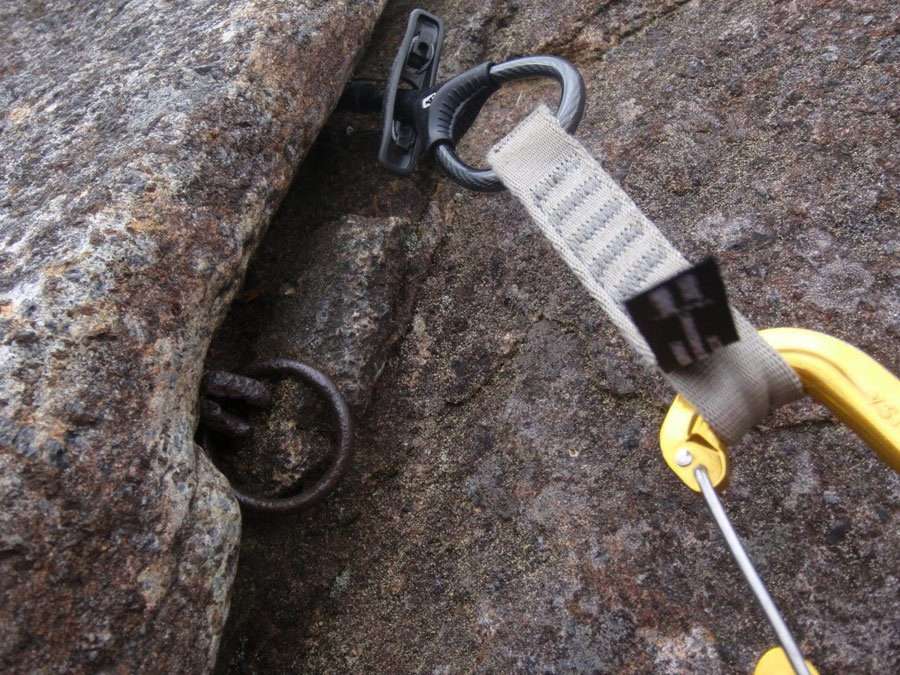

During the summer someone had removed an old ring piton on the fifth pitch of Empress. I’ve climbed Empress dozens of times and always enjoyed seeing this artifact in a crack high on the slab. No doubt other climbers felt the same.

In his prime, Wiessner was perhaps the best rock climber in the country. Even if he didn’t hammer the piton into the rock himself, the rusty piece of iron harked back to an era when climbers scaled cliffs in mountain boots or felt-soled shoes while dragging a hemp rope tied around the waist.

The next day I returned to Chapel Pond Slab and discovered that another old ring piton was missing from the fifth pitch of Bob’s Knob Standard, another historical route. The leader in the first ascent of this route, also in 1933, was John Case, one of the first to introduce European climbing techniques to the United States. He served as president of the American Alpine Club from 1944-46.

No one knows who placed the pitons or when. However, they were of antique vintage, probably made before World War II or soon after.

RELATED: Climbers retrace history on Chapel Pond Slab

“They were ancient when I arrived in 1977,” said Don Mellor, author of Climbing in the Adirondacks and American Rock. “They are archival, communal artifacts. … Taking these is wrong.”

Not only is it wrong; it very well might be illegal. State education law forbids the removal from state land of “any object of archaeological, historical, cultural, social, scientific or paleontological interest.” The state Department of Environmental Conservation once informed the Adirondack Explorer that collecting old beer cans on the Forest Preserve violated the law. Evidently, beer cans qualify as historical artifacts. Surely a piton left by an early rock climber holds as much cultural significance as a beer can tossed in the woods.

Pitons

Pitons are seldom used today. In the past, climbers would hammer them into cracks and clip their ropes to them for protection against a fall. Early pitons, such as ring pitons, were made of malleable iron. It’s difficult to remove such pitons without damaging them. That could be why climbers left them behind on Empress and Bob’s Knob Standard. Modern pitons are fashioned from sturdier metal and are easier to remove for reuse. (An angle piton of more recent vintage also was removed from the first pitch of Empress.)

If you happen to see a ring piton on a climb, you’re likely on a very old route. That piece of iron is a piece of history. Reflect a moment on those who came before you, who scaled cliffs without modern equipment such as nylon ropes, belay and camming devices, or shoes with sticky-rubber soles. Reflect, and then climb on.

Looking for hiking inspiration?

Sign up for one (or more) of our daily and weekly newsletters and we’ll send you a free guide of short hikes around the region, compiled from our popular “Short Hikes” guidebook series.

"explorer" - Google News

September 28, 2021 at 08:26PM

https://ift.tt/3CQs5AE

The case of the stolen climbing pitons - Adirondack Explorer

"explorer" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2zIjLrm

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "The case of the stolen climbing pitons - Adirondack Explorer"

Post a Comment