American whiskeys are distinctive from their Scottish counterparts in one very distinctive way: they leave behind an unusual web-like pattern as droplets dry up, and those webs are different for different brands—making them a kind of "fingerprint." That's a property that can be used not only to tell the difference between brands of American whiskeys but could one day lead to an effective method for the identification of counterfeits, according to a new paper published in ACS Nano.

As we reported last year, Stuart Williams, a professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Louisville in Kentucky, noticed one day that if he diluted a drop of bourbon and let it evaporate under carefully controlled conditions, it formed what he terms a "whiskey web": thin strands that form various lattice-like patterns, akin to networks of blood vessels. Intrigued, he decided to investigate further with different types of whiskey—plus a bottle of Glenlivet Scotch whisky for comparison. It was the perfect project for his sabbatical leave to study colloids (suspended particles in a medium, like Jell-O, whipped cream, wine, and whiskey) at North Carolina State University.

Fundamentally, it's the same underlying mechanism as the "coffee ring effect," when a single liquid evaporates and the solids that had been dissolved in the liquid (like coffee grounds) form a telltale ring. It happens because the evaporation occurs faster at the edge than at the center. Any remaining liquid flows outward to the edge to fill in the gaps, dragging those solids with it. Mixing in solvents (water or alcohol) reduces the effect, as long as the drops are very small. Large drops produce more uniform stains.

In those earlier experiments, Williams tested 66 American whiskeys; only one did not create a web. Whiskey webs appear to be related to alcohol content. Williams and his team had to dilute the whiskeys with water down to about 40-50 percent proof. Specifically, they found that if the alcohol-by-volume level was above 30 percent, there would only be a uniform film; lower than 10 percent, and you get the coffee ring pattern. It's only at an intermediate alcohol-by-volume level of between 20 percent and 25 percent that you get these unique webby structures.

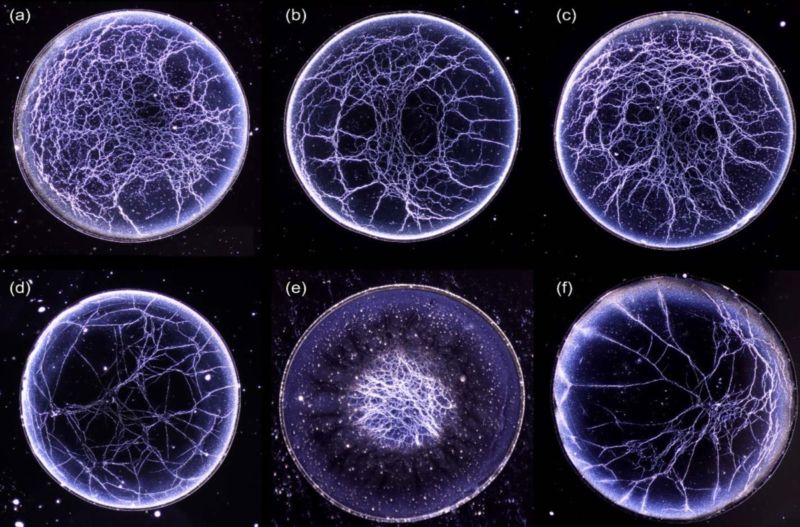

The next step was to try to identify the specific chemicals responsible to see if the patterns could be used as fingerprints for specific brands. For this latest set of experiments, his lab tested 66 American whiskeys (56 bourbons, 10 others), 13 other whiskeys, and six un-aged whiskeys, all subjected to the same testing conditions: 25 percent alcohol by volume and a 1 millimeter droplet. "To date, we have tested close to 100 samples, and we have yet to find a non-American whiskey to form a web under these conditions," said Williams.

The kinds of solids that are present in the whiskeys also contribute to the webby pattern left behind. For instance, whiskeys aged in new charred barrels typically have more of those solids, especially those that readily dissolve in ethanol. "We believe that the increased solids extracted from American whiskeys is responsible for these patterns," said Williams. "The chemicals originate in the fermentation and distillation, but really undergo dramatic changes during maturation."

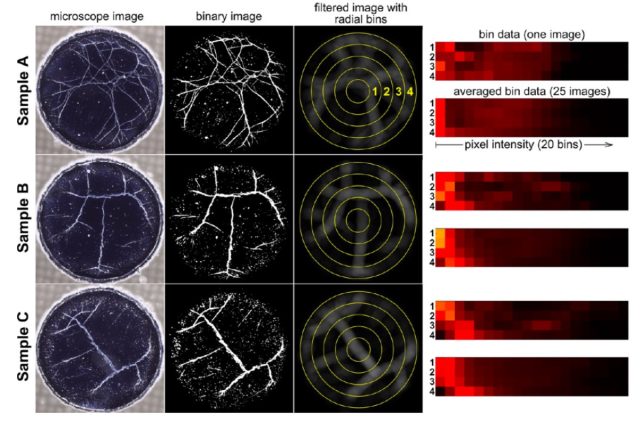

Next, Williams conducted an aggregated pattern ID test to confirm that the distinctive web patterns for different brands was repeatable. He used three brands of whiskey from the same distillery in the experiment: Old Weller Antique, W.L. Weller 12 Year, and W.L. Weller Special Reserve. He and his team tested 30 drops of each (90 drops total, all about 2 millimeters in diameter, or "the size of a very large period") and took digital images of each.

Then they randomly choose 25 drops from the same whiskey and averaged the results to create a representative "library" measurement for that whiskey for future comparison purposes, per Williams. "We compared the remaining drops to this whiskey library," he said. "A whiskey was successfully matched with its brand 90 percent of the time."

For another experiment, Williams spiked a "control whiskey" with chemicals like vanillin, tannin, or lignin (all flavor compounds) and found there was a distinct change in the resulting whiskey web pattern. "This provides evidence that the chemicals associated with flavor impact the final structures," he said. "In other words, each whiskey buckles differently because the chemicals that make up their monolayer are different. Thus, the resulting web structure is reflective of its contents."

Williams was also able to produce the web pattern for non-American whiskeys by spiking the water-ethanol liquid with fatty acids and by performing the test on a highly water-repellant surface, so that the droplet beaded up very well.

The real question is whether it's possible to tell the difference between old and young whiskey (or good and bad) simply by evaporating a distilled drop under the right ambient conditions. That way the technique could be used for quality control in distilleries or for detecting counterfeits. Preliminary results were promising, but whiskey chemistry is incredibly complicated, containing thousands of chemicals.

"Unfortunately, we will not be able to tell a whiskey's composition using this analysis," said Williams. "But we can use this technique to determine if it is an American whiskey or not, i.e., whether it forms a web or not." Even more statistical analyses are needed, with an aim toward standardizing testing procedures, before the technique will be useful for differentiating between different American whiskeys. And while it won't replace more sophisticated chemical techniques, such as chromatography, it might prove useful as a simple pre-analysis test to determine if it's worth doing a more expensive and time-consuming chemical test.

Since Williams, like almost everyone else these days, is largely working from home, he has used that time to work on developing a smartphone-based visualization platform so that everyone can make and image their own whiskey webs at home, with little more than an inexpensive lens (which runs around $7 on Amazon) or a USB microscope (which costs about $20). He expects to post instructions on his research website (which also includes a gallery of whiskey-web images) in time for this weekend, in case cabin fever is getting to you and you're looking for a fun DIY project.

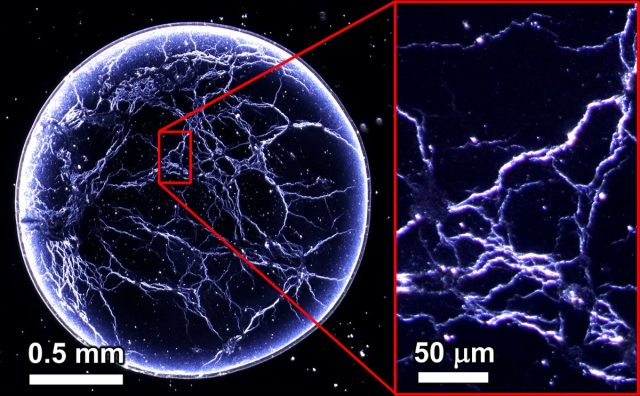

That said, "The best images are done on a standard light microscope," said Williams. "The light needs to come in from the side—the illuminated structures in these images are reflecting light. You may notice that the image is mostly black with the features being white. These features are reflecting light to the camera."

DOI: ACS Nano, 2020. 10.1021/acsnano.9b08984 (About DOIs).

https://news.google.com/__i/rss/rd/articles/CBMidGh0dHBzOi8vYXJzdGVjaG5pY2EuY29tL3NjaWVuY2UvMjAyMC8wMy93aGlza2V5LXdlYnMtc2VydmUtYXMtZmluZ2VycHJpbnRzLXRvLWRpc3Rpbmd1aXNoLWJldHdlZW4tYW1lcmljYW4td2hpc2tleXMv0gF6aHR0cHM6Ly9hcnN0ZWNobmljYS5jb20vc2NpZW5jZS8yMDIwLzAzL3doaXNrZXktd2Vicy1zZXJ2ZS1hcy1maW5nZXJwcmludHMtdG8tZGlzdGluZ3Vpc2gtYmV0d2Vlbi1hbWVyaWNhbi13aGlza2V5cy8_YW1wPTE?oc=5

2020-03-25 12:00:00Z

52780688070737

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Forget that tired-old coffee ring effect: “Whiskey webs” are the new hotness - Ars Technica"

Post a Comment