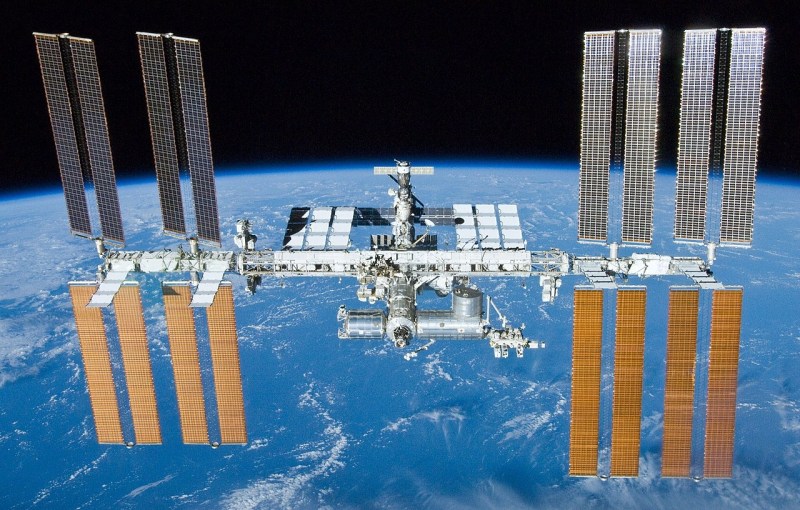

Aboard the International Space Station (ISS), humanity has managed to maintain an uninterrupted foothold in low Earth orbit for just shy of 20 years. There are people reading these words who have had the ISS orbiting overhead for their entire lives, the first generation born into a truly spacefaring civilization.

But as the saying goes, what goes up must eventually come down. The ISS is at too low of an altitude to remain in orbit indefinitely, and core modules of the structure are already operating years beyond their original design lifetimes. As difficult a decision as it might be for the countries involved, in the not too distant future the $150 billion orbiting outpost will have to be abandoned.

Naturally there’s some debate as to how far off that day is. NASA officially plans to support the Station until at least 2024, and an extension to 2028 or 2030 is considered very likely. Political tensions have made it difficult to get a similar commitment out of the Russian space agency, Roscosmos, but its expected they’ll continue crewing and maintaining their segment as long as NASA does the same. Afterwards, it’s possible Roscosmos will attempt to salvage some of their modules from the ISS so they can be used on a future station.

This close to retirement, any new ISS modules would need to be designed and launched on an exceptionally short timescale. With NASA’s efforts and budget currently focused on the Moon and beyond, the agency has recently turned to private industry for proposals on how they can get the most out of the time that’s left. Unfortunately several of the companies that were in the running to develop commercial Station modules have since backed out, but there’s at least one partner that still seems intent on following through: Axiom.

This close to retirement, any new ISS modules would need to be designed and launched on an exceptionally short timescale. With NASA’s efforts and budget currently focused on the Moon and beyond, the agency has recently turned to private industry for proposals on how they can get the most out of the time that’s left. Unfortunately several of the companies that were in the running to develop commercial Station modules have since backed out, but there’s at least one partner that still seems intent on following through: Axiom.

With management made up of former astronauts and space professionals, including NASA’s former ISS Manager Michael Suffredini and Administrator Charles Bolden, the company boasts a better than average understanding of what it takes to succeed in low Earth orbit. About a month ago, this operational experience helped secure Axiom’s selection by NASA to develop a new habitable module for the US side of the Station by 2024.

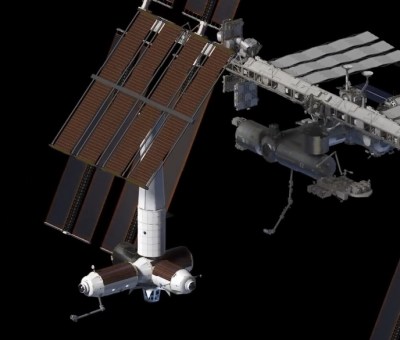

While the agreement technically only covers a single module, Axiom hasn’t been shy about their plans going forward. Once that first module is installed and operational, they plan on getting NASA approval to launch several new modules branching off of it. Ultimately, they hope that their “wing” of the International Space Station can be detached and become its own independent commercial station by the end of the decade.

The First Piece of the Puzzle

The module Axiom will build as part of the recently announced agreement with NASA will be called “Axiom Node One”, or AxN1. It will be a slightly larger version of the design used for the existing Harmony and Tranquility nodes. These cylindrical nodes not only provide living and working environments, but act as vital junctions for expanding the Station. Each one features six Common Berthing Mechanism (CBM) ports that can either be used temporarily for resupply spacecraft such as the SpaceX Dragon or as a permanent mount point for another module. They cannot however be used for crewed spacecraft such as Russia’s Soyuz or the Boeing CST-100 Starliner, as those vehicles use active docking ports that are faster to disconnect in the event of an emergency.

The AxN1 node is also planned to include a so-called “Earth Observatory” module, envisioned as a larger version of the Station’s existing Cupola. Rather than being a simple window, the Observatory will be deep enough to allow crew members to enter and move around in. During flight the Observatory will be attached to the forward CBM port of the AxN1, and after it’s been attached, the Station’s robotic arm will move it to the node’s nadir (Earth-facing) CBM port.

But before it can be installed, things will need to get rearranged slightly. The plan is to berth AxN1 to the front of the Harmony mode, but that’s currently where the second Pressurized Mating Adapter (PMA-2) is installed. This recent video released by Axiom shows how they propose to attach their modules to the ISS, but it starts with PMA-2 already removed and out of sight (the PMA seen on top of Harmony in the video is actually PMA-3).

This device converts a CBM into a docking port for crewed spacecraft, which is obviously a capability the Station requires to function. So the PMA-2 will need to be relocated before the arrival of AxN1, it’s just not immediately clear where it’s going to go.

Packing Up and Moving Out

Assuming all goes according to plan with AxN1 and the ISS program gets the expected extension, the company plans to launch their second module in 2025. Called “Axiom Habitation Module One” or AxH1, this module will only have ports on either end and devote most of its internal volume to crew accommodations. Rendered images show the inside of AxH1 offering high-tech luxury not unlike something from 2001: A Space Odyssey, though it seems likely the final module would have a somewhat more utilitarian appearance for practical reasons. The following year, the pair of modules would be joined by the “Axiom Research and Manufacturing Facility” (AxRMF).

If this seems like a breakneck pace to launch and install new Station modules, that’s because it is. By the time AxN1 and AxH1 get installed, retirement of the ISS may only be two or three years away. If the company has any chance of using the existing Station infrastructure as a springboard to help get their own self-sustaining segment built, they’ll need to move fast.

Before this hypothetical Axiom commercial space station could break free of the ISS and operate independently, it’s going to need power. Concept art of the Axiom modules show they will all feature integrated solar panels to support basic functionality, but performing any kind of useful science or manufacturing aboard the station will require more energy then they can provide. There also needs to be a way for the station to dissipate all of the heat generated by the humans and equipment onboard.

So the long term-plan is to add an extendable module with its own large photovoltaic array and thermal radiators to take over once the ISS is gone. As this array would potentially be deployed before the Axiom segment separates, it would mount to the zenith (space-facing) port of AxN1 and extend vertically so it won’t interfere with the solar panel “wings” of the Station.

Open For Orbital Business

Axiom’s plan has a lot of steps that need to happen very quickly, and success is far from guaranteed. But assuming everything works out and nobody beats them to the punch, by 2030 the company should be the proud owner of the world’s first commercial space station. It would be a phenomenal technical achievement, and a historic moment as far as the democratization of space goes. But for a commercial outpost to make sense there obviously needs to be customers. So who’s paying?

With crew compartments that look like they were inspired by science fiction and an Observation deck large enough for multiple people to float freely inside, there’s no question Axiom has their eyes on space tourism. If the likes of Mark Shuttleworth and Richard Garriott were willing to pay tens of millions of dollars to spend a few days aboard the International Space Station, a destination that features all the comforts and luxuries of a ship’s engine room, the potential ticket price for a true “Space Hotel” could be enormous.

But there are very few individuals who could afford such an opportunity, and of them, only a small percentage would be willing to actually strap into a rocket and make the trip. There’s little doubt that a few more wealthy tech entrepreneurs would be willing to book a short stay aboard, but that alone isn’t going to be enough to cover the cost of building and operating the station.

Somewhat ironically, Axiom’s biggest customer in the foreseeable future will likely end up being NASA. The retirement of the International Space Station doesn’t mean an end to science in low Earth orbit, it just means it will have to be done somewhere else. All of that research that NASA either performs themselves or orchestrates for other agencies will need a new home, and the Axiom station could be where it ends up.

The agency currently spends $3-$4 billion each year to maintain and support the ISS, representing about half of their annual human spaceflight budget. If even a fraction of that could be earmarked for purchasing time on a commercial space station after 2030, then commercial operators like Axiom will have at least one heavyweight customer they can count on.

https://news.google.com/__i/rss/rd/articles/CBMiY2h0dHBzOi8vaGFja2FkYXkuY29tLzIwMjAvMDMvMDMvZXhwYW5kaW5nLWFuZC1ldmVudHVhbGx5LXJlcGxhY2luZy10aGUtaW50ZXJuYXRpb25hbC1zcGFjZS1zdGF0aW9uL9IBAA?oc=5

2020-03-03 15:01:00Z

52780639972188

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Expanding, And Eventually Replacing, The International Space Station - Hackaday"

Post a Comment